Reading books with dragons on the cover says something about a guy.

In high school, the fact that I elected to read novels in my spare time sent a message of its own, never mind the cover art. Other than a debate with another student over which books were better sellers, those that comprised the Dragonlance series or the works of John Saul, I didn’t get much guff from my peers for reading fantasy fiction.

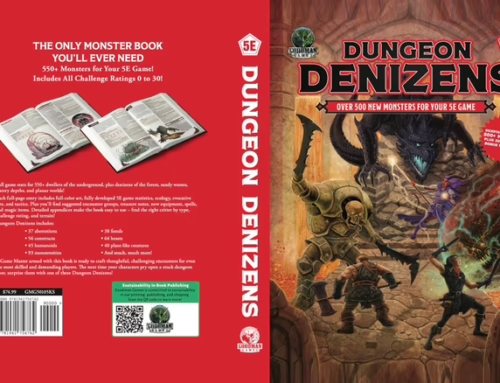

This book, which I read as a sophomore in high school, opened the door to a life of reading and writing fantasy fiction.

No, it wasn’t until college that I got my first real taste of genre bias. As an English major, I earned college credits for writing a sword-and-sorcery short story and the opening chapters of my first fantasy novel. However, in my sophomore year, I took a writing workshop where one rule not so much rained on my parade as washed it away in a deluge of biblical proportions: no genre fiction.

For my first assignment, I churned out a quasi-autobiographic “campus life” short that was an interesting exercise inasmuch as I found myself—for the first time in a very long time—writing scenes that took place in modern-day Earth. At the same time, it was a dull plot that satisfied the letter of the law, if not the spirit of it. My classmates gave it passable reviews.

Weeks later, I critiqued a classmate’s short story that followed an arguably familiar path: a college student dealing with relationship problems. Blah blah blah. When the professor questioned my criticism on the basis that my own story suffered from similar problems, my retort went something like this:

“My story was boring because I wasn’t able to write what I wanted to due to the ‘no genre fiction’ rule.”

To my delight, the professor repealed that unjust decree, and I was able to submit more chapters from The Renegade Chronicles, which got better feedback than my obligatory stab at writing a more realistic (and more mundane) story. And I would argue that the rest of the class’s offerings were richer and more enjoyable—to me, at least—once the restriction was lifted.

Nevertheless, I never rid myself of the feeling that academic types—including most professors and a good many of the students—looked down on my interest in (gasp!) genre fiction. Whether science fiction, romance, mystery or Western, true artistes don’t dabble in anything as juvenile as genre fiction. Real literature is about realistic people in realistic situations doing perfectly normal things.

Yawn.

I was wont to tell the anti-genre contingent that modern (non-genre) literature didn’t generally interest me because I get enough real-life troubles in real life without willingly submitting myself to stories about people whose problems come woefully close to the mark. In many cases, I find these books lacking in creativity because of that fact.

Now don’t get me wrong. There’s a reason why various genres get a bad name—namely, clichés. Some writers use genre tropes as a paint-by-number template for storytelling. Those who don’t “get” fantasy fiction, for example, dismiss it because it can be very formulaic: Chosen One + motley companions + two-dimensional evil guy = every fantasy novel you’ve never read. Multiply by the square root of “magical sword,” and you might get a movie deal out of it.

Clearly, “speculative fiction” isn’t inherently more creative than its non-genre cousins.

So here’s the thing: there are well-written Westerns and poorly written ones, brilliant non-genre novels and agonizingly uninspired ones. Genre—or lack thereof—doesn’t determine the merit of fiction.

While most genres provide no shortage of shortcuts for writers to take and a plethora of stereotypes for them to try to pass off as interesting and fresh, it’s no more fair to say all genre fiction favors whimsy over substance than it is to declare all non-genre fiction is dull.

It still rankles me when someone—and fellow writers, no less—dismisses fantasy and science fiction as a waste of time because it couldn’t possibly be relatable to readers. The existence of magic or advanced technology in a tale does not preempt the inclusion of the themes we humans have grappled with since time immemorial.

The good news is that discerning readers don’t need to choose between high-quality genre fiction and fantastic non-genre fiction because examples from both categories contain no shortage of pathos and creativity. With so many talented genre and non-genre writers out there, we can have the best of both worlds.

And sometimes those worlds just happen to have dragons.

Thank you. I’ve only recently started running into the anti-genre attitudes, and it rankles. It’s nice to hear a good, thought out reply to the stupidity.

I didn’t necessarily want to “go there” in the blog post, but I’ve long suspected that the academic types turn up their noses at genre fiction because of its commercial success. Even if a prof publishes a non-genre novel, sales tend to be modest at best. Because there’s a wider-reaching audience with genre fiction (a good and bad thing), I believe it’s easier for a genre fiction writer to make a living at writing than a non-genre fiction.

In some cases, they just might be rankled that “the masses” are more apt to buy and read tales of dragons and wizards than another “slice of life” novella about coping with “X” in the modern world.

I could be completely wrong about this, however.

Read the latest, David. Compelling to a degree. I still think that “real life” fiction is harder to do than “make up” fiction. There are always new twists to the human condition, if you look for them.

As always, friend, I stand in awe of how well your write these blogs, whatever. Fantastico!

Wonder. Maybe you should think on a non fiction book. You come across so well in this instructional kind of prose.

Your friend,

Tomas.

Tom,

I think we’re going to have to agree to disagree on your comment about writing “real life” fiction being more difficult than speculative fiction. If your writing is set in modern-day Earth, most of the work in terms of setting is done for you. Oh sure, you’ll need to do some research to make sure things are accurate, but you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. If your novel is set on Earth in the past, then even more research is required to see how life was like back then.

So much of writing sci-fi and fantasy is spent building a world from the ground up. Yes, you borrow bits and pieces from Earth’s cultures (past and present), but to do it well, you have to dedicate an awful lot of time to mapping out the past and the present. And after you do that, you have to be your own referee, making sure everything fits together and is consistent.

As someone who has written fiction in both the modern world and a world of my own creation, I can definitively say that drafting scenes in the former presents fewer challenges on a superficial level.

Think of it this way, if I write a scene set in present-day Earth wherein a character uses a cell phone, I don’t have to waste too many words explaining how this technology works. But if I write about long-distance communication in a scene set in an alien world, I have to determine how the tech works, write a paragraph (or more) describing the device and how it works, and then make sure that in all subsequent scenes the tech functions the same way.

When you write using a vocabulary the reader already possesses, you don’t have to spend as much time explaining.

But maybe this aspect of writing isn’t what you mean by “real life” fiction being harder?

David my lad,

You are “Inventing” new worlds? How many of these new worlds have you gleaned from reading other SF/fantasy novels?

Enough. I compliment your exquisite prose, and you snap at me.

Yous gonan done i t, man.. Hurted my feelings.

TOM

Oh, the setting of my first fantasy series is clearly inspired by pre-existing worlds. No arguing that. I started crafting that world back when I was 12, so I did borrow heavily from pre-established tropes.

But that doesn’t mean I didn’t put in the time (nearly one million words alone) to make it my own.

I do thank you for the praise for my prose, but it’s hard not to see it as a back-handed compliment when there’s always the implied proviso “too bad you’re wasting your time with that fantasy crap.” I shouldn’t be so defensive perhaps. I was merely trying to explain why good writing is good writing regardless of genre.

I can see now that I won’t be able to convince you to give speculative fiction a fair shake, so I won’t waste any more words on that front. To each his own, right?

Truce!